A picture book is greater than the sum of text and pictures. It may seem self-evident, but isn’t always true, and is a crucial ingredient in a picture book that really works.

A picture book is greater than the sum of text and pictures. It may seem self-evident, but isn’t always true, and is a crucial ingredient in a picture book that really works.

Growth to something new through bonding of separate creative elements words, pictures and design – makes picture books, for me, particularly invigorating to write. In a novel you manipulate imagination and skills on your own.

In picture books there is the artist, bringing unknown dimensions and possibilities. The open-endedness of that is marvellous. Words and pictures result in two visions merged and reborn as a single entity through the mediating vision of the editor selecting the text in the first place, creating the partnership, and guiding all with an eye for the hidden rocks.

A difficult task. Books have foundered on an author’s unhappiness with an artist’s conception. But pictures that merely illustrate, however effectively, result in a disappointing book. Glorious pictures with a limp text don’t work either. In a good picture book, words and pictures reflect each other, but go further. True picture book artists bring a new insight, sometimes with a subtext and proliferating subplots never originally dreamed of by the writer.

Children respond in powerful ways to these visual worlds, succumbing to the magic of storytelling (and on to the magic of language) wanting to know more, to explore every corner of the picture, to get to the end of the story, hear it again ultimately to read it for themselves. Layers of meaning reside not only within words and pictures, but in that critical linking of the two.

In Suzi Sam George and Alice, I used a recurring phrase ‘time for George to rest’. It conveys the image of a tired cat. The artist Sally Gardner’s languid George draped around telephones, toy boxes, watering cans, even in the oven, gives instantly the intrusive  of his centre stage, egocentric laziness and the unpredictable domestic chaos created by the two kids and their cats.

of his centre stage, egocentric laziness and the unpredictable domestic chaos created by the two kids and their cats.

And there’s a critical aspect of the editor’s role here to ensure subplots don’t obliterate the central conception of the story, part of the partnership between all parties to a picture book’s birth: editor at the centre, but the designer too working to achieve a harmonious page that does justice to the enlarged whole.

Writing a picture book is in a very real sense, only the beginning. Structure, meaning, characters,setting will be reinvented by someone who deals in visual images, not words.

For the writer there is an enormous danger in assuming that what you write will be literally ‘illustrated’, and then feeling disappointed when the artist doesn’t. Start from here, and you’re heading for a bad picture book, intrinsically limited by a strait jacket imposed on visual skills by non-visual skills. Picture books are nerve wracking for some writers. Will the artist take over? Will the story be undermined? Will the book become something they no longer recognize or like? It is not an anxiety I share, but I recognize the problem.

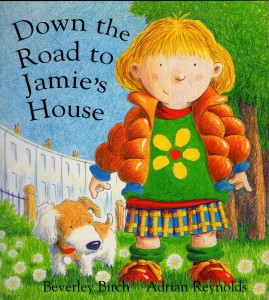

Obviously the author must agree to the choice of artist. The artist needs to take on the author’s text with enthusiasm, feeling that it is right for them. Here, again, the vision of the editor is at work: who is right for this one? Adrian Reynolds illustrated Down the road to  Jamie’s House. I knew and loved his artwork already, but I was unprepared for the instant meshing of his ideas with mine. Adrian’s Annie is someone I recognized at once in every aspect of her shape, looks, gestures.

Jamie’s House. I knew and loved his artwork already, but I was unprepared for the instant meshing of his ideas with mine. Adrian’s Annie is someone I recognized at once in every aspect of her shape, looks, gestures.

When I start to write I do have pictures in my head. But I also know that I need to stay open to variation and experiment, be prepared to rework areas of the text if the artist’s insight suggests something not originally envisaged. This ‘reworking’ may mean breaking the text between pages differently. Or teasing out a section of text to allow room for another picture: as in The Village in the Forest by the Sea,  where I made room for Angela Chidgey’s enthusiasm for the beauty of the Kenyan coast.

where I made room for Angela Chidgey’s enthusiasm for the beauty of the Kenyan coast.

Or I may need to change something. In Down the road to Jamie’s House, Annie is suddenly terrified in an unfamiliar park. My original text talked of

‘Tall trees, dark trees, whispering trees, sighing.

Split! Splat! Raindrops plopping, splashing Annie’s face.

Bushes crouching, hissing in the rain.’

Adrian’s picture showed no bushes. Dark trees leaning across a tiny girl. But no bushes. The scene is profoundly menacing. I had no hesitation in jettisoning the crouching bushes (much as I liked them) and reworking the last three lines. Now there are ‘shadows hissing in the rain’.

The recognition of the rightness of an artist’s conception, like finding a picture book idea in the first place, remains an infinitely mysterious thing for me. Children ask, Where do ideas come from? I don’t know. Once, as I woke, there was an idea that took firmer and firmer shape and then shot out of my head on to paper as a new picture book text, all in the space of an hour or two. But in what corner of my head it had been nestling, and what triggered it, I have no idea.

In my most recent picture books – Turtle’s Party in the Clouds (truly vibrant pictures by Christine Jenny), and Greedy Anansi and his Three Cunning Plans, (equally richly illustrated by Alexander Jansson), I had that same instant sense of recognition in seeing

In my most recent picture books – Turtle’s Party in the Clouds (truly vibrant pictures by Christine Jenny), and Greedy Anansi and his Three Cunning Plans, (equally richly illustrated by Alexander Jansson), I had that same instant sense of recognition in seeing  the artists’ conceptions, and of the ‘bigger’ story their vision made of the originals.

the artists’ conceptions, and of the ‘bigger’ story their vision made of the originals.

What I do know is that possessiveness, an author’s sense of the picture book as ‘mine’, impedes fruitful development. An artist always brings something of self. As writer, you need to be open and welcome that. Together we have to create something that is read and reread (awful as a parent to have to return to a limp text!). Our picture book may offer reassurance, take off on wings of imagination, new ideas, words, sounds, a good laugh … or if it is rich enough, all of these things. We have such a wonderful heritage in picture books, constantly joined by new books which take my breath away. Using them with children, seeing how they respond, always reawakens my effort to try in partnership with the artists to reach for that quality in our books.